-Thank goodness for Obamacare. Whoever said “G” isn’t important to national output?!

-I liked this FRBNY chart (h/t Marc Faber):

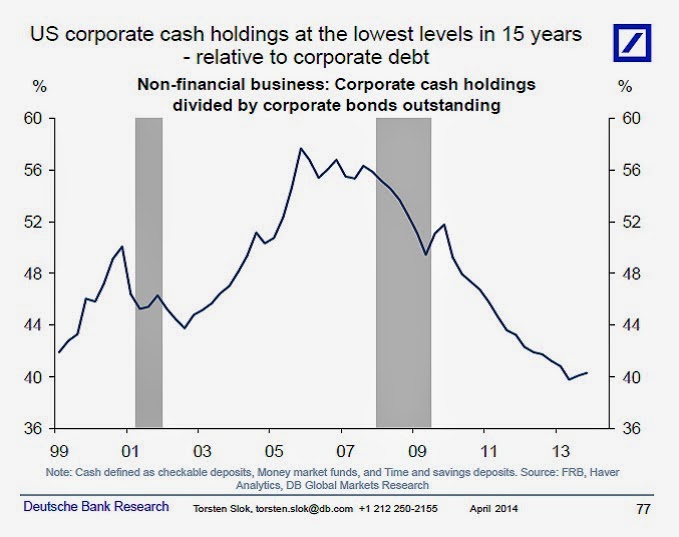

-I’ve said it before, I’ll say it again. You can’t just look at the asset side of the balance sheet…

-This is what a “failed rally” looks like… (h/t Fleck)

-“Every act of conscious learning requires the willingness to suffer an injury to one’s self-esteem. That is why young children, before they are aware of their own self-importance, learn so easily; and why older persons, especially if vain or important, cannot learn at all.” –Thomas Szasz (h/t Marc Faber)

-“…agonies notwithstanding, I do not believe in mistakes. I believe that we all go through some very bad experiences and that the only mistake we can make is to fall down and to stay down.” – Marc Faber

Wednesday, April 30, 2014

Monday, April 28, 2014

More on the Setting Sun

In this week’s letter from James Gruber, he provides a nice summary of all the elements working against Japan right now. And argues that inflation is on its way – in large part because wages are set to rise.

I’ve discussed a few times how much I think of Kyle Bass as an investor. Here is a recent presentation posted online. Among other things, he talks about how the Yen has a lot more room to drop and the reasons why.

I’ve discussed a few times how much I think of Kyle Bass as an investor. Here is a recent presentation posted online. Among other things, he talks about how the Yen has a lot more room to drop and the reasons why.

Sunday, April 27, 2014

Saturday, April 26, 2014

The Death of Money

The subtitle is The Coming Collapse of the International Monetary System and the author is James Rickards (2014).

From the same writer as Currency Wars, the subtitle should give it away – he looks at the dynamics at play that will undermine the existing structure, specifically dollar supremacy. All of it presages financial war, a state where efficient markets theory and rational behavior can be thrown out the window. Unfortunately, politicians, central bankers and the like rely on theories and models that in no way reflect the complexity theory that governs the real world – in part, because a complex world can seem noncritical up until the moment that all hell breaks loose. Hence the reason that so many “experts” struggle to see crises in advance. And this sense of confidence in their understanding of the world is what encourages these central planners to take a top-down approach of managing and fine-tuning all elements of the economy. All leading to their eventual downfall. Beyond these larger ideas, though, Rickards provides interesting analysis on a few specific topics.

The first is an explanation of why so many “Euroskeptics”, expecting the currency to combust any day now, have been wrong. First, in a world where the U.S. has been forcing a weak dollar policy, it should not come as a shock that the Euro would gain relative strength. Second, the currency’s strength is more related to capital flows and central bank policy, and is not at the mercy of a particular bond default – so the issues with Greek and Spanish bonds does not predict with any certainty what might happen to the Euro. Third, even as export competitiveness went down in Europe, the U.S. and China were involved in swaps with the ECB and sending money into Europe in the form of FDI, thereby supporting the currency. Fourth, there exists a belief in Keynesian theory, specifically in the notion of sticky wages and that inflation is needed to lower real unit labor costs and to avoid a liquidity trap. Well, Europe has seen wages go down, and the result has been a lack of need or desire to break free from the Euro and return to national currencies that encouraged inflation and corruption. Finally, as the Euro is a political project, the will to stick with it is much greater than many analysts realize. I don’t necessarily subscribe to all these points, but feel they are worth highlighting.

The second subject is the way to think about Debt-to-GDP ratios. In the end, what is most critical is not the absolute level of that ratio, but its trend towards sustainability. Which is to say that the use of debt must be for productive ends, thereby creating economic output (net of interest expense) that is measurably in excess of the primary deficit. For countries like the U.S. and Japan, the trend is not their friend – especially as the use of debt by government in the QE and Abenomics programs is for non-productive ends.

As a corollary of that discussion, Rickards brings up a topic that has intrigued me for a while and generated thoughts in other posts on this site – namely, about a true understanding of the period referred to as the “Golden Age of Keynesianism” following WW2 until 1971. I have said that a Minsky analysis of that time would reveal, simply, that the trend towards reckless and speculative behavior was slowed only because the Depression and war had led to a very high level of savings in this country that took a longer time to burn through – the Keynesians simply try to take credit where no credit is due. Rickards’ view is similar – that financial repression was allowed to go on for a longer period of time before inflation took off because so many were living with recent memories of the Depression and wartime controls and rationing, thus keeping a very large portion of their money in banks.

The final topic is around why deflation is so problematic – from the point of view of politicians and central bankers. First, under deflation, the government debt burden becomes greater in real terms, making it more difficult to repay. Second, as an off-shoot of the first, the Debt-to-GDP ratio would move against governments in such times (since debts would go up, but economic growth would go down), thereby leading to higher interest rates and even larger deficits. Third, as deflation causes the real burden of debt to go up, it stands to benefit creditors – until defaults go up as a result, and bank failures follow. Fourth, real wages go up even as nominal wages stay constant – and from a tax collection standpoint, the government is not able to monetize that benefit. Inflation is the easy way, even if it just delays the day of reckoning. All worth keeping in mind, I think , any time you hear an economist or politician prattle on.

As a last anecdote, the author speculates that $9,000 per ounce for gold is closer to fair value given the global money supply.

From the same writer as Currency Wars, the subtitle should give it away – he looks at the dynamics at play that will undermine the existing structure, specifically dollar supremacy. All of it presages financial war, a state where efficient markets theory and rational behavior can be thrown out the window. Unfortunately, politicians, central bankers and the like rely on theories and models that in no way reflect the complexity theory that governs the real world – in part, because a complex world can seem noncritical up until the moment that all hell breaks loose. Hence the reason that so many “experts” struggle to see crises in advance. And this sense of confidence in their understanding of the world is what encourages these central planners to take a top-down approach of managing and fine-tuning all elements of the economy. All leading to their eventual downfall. Beyond these larger ideas, though, Rickards provides interesting analysis on a few specific topics.

The first is an explanation of why so many “Euroskeptics”, expecting the currency to combust any day now, have been wrong. First, in a world where the U.S. has been forcing a weak dollar policy, it should not come as a shock that the Euro would gain relative strength. Second, the currency’s strength is more related to capital flows and central bank policy, and is not at the mercy of a particular bond default – so the issues with Greek and Spanish bonds does not predict with any certainty what might happen to the Euro. Third, even as export competitiveness went down in Europe, the U.S. and China were involved in swaps with the ECB and sending money into Europe in the form of FDI, thereby supporting the currency. Fourth, there exists a belief in Keynesian theory, specifically in the notion of sticky wages and that inflation is needed to lower real unit labor costs and to avoid a liquidity trap. Well, Europe has seen wages go down, and the result has been a lack of need or desire to break free from the Euro and return to national currencies that encouraged inflation and corruption. Finally, as the Euro is a political project, the will to stick with it is much greater than many analysts realize. I don’t necessarily subscribe to all these points, but feel they are worth highlighting.

The second subject is the way to think about Debt-to-GDP ratios. In the end, what is most critical is not the absolute level of that ratio, but its trend towards sustainability. Which is to say that the use of debt must be for productive ends, thereby creating economic output (net of interest expense) that is measurably in excess of the primary deficit. For countries like the U.S. and Japan, the trend is not their friend – especially as the use of debt by government in the QE and Abenomics programs is for non-productive ends.

As a corollary of that discussion, Rickards brings up a topic that has intrigued me for a while and generated thoughts in other posts on this site – namely, about a true understanding of the period referred to as the “Golden Age of Keynesianism” following WW2 until 1971. I have said that a Minsky analysis of that time would reveal, simply, that the trend towards reckless and speculative behavior was slowed only because the Depression and war had led to a very high level of savings in this country that took a longer time to burn through – the Keynesians simply try to take credit where no credit is due. Rickards’ view is similar – that financial repression was allowed to go on for a longer period of time before inflation took off because so many were living with recent memories of the Depression and wartime controls and rationing, thus keeping a very large portion of their money in banks.

The final topic is around why deflation is so problematic – from the point of view of politicians and central bankers. First, under deflation, the government debt burden becomes greater in real terms, making it more difficult to repay. Second, as an off-shoot of the first, the Debt-to-GDP ratio would move against governments in such times (since debts would go up, but economic growth would go down), thereby leading to higher interest rates and even larger deficits. Third, as deflation causes the real burden of debt to go up, it stands to benefit creditors – until defaults go up as a result, and bank failures follow. Fourth, real wages go up even as nominal wages stay constant – and from a tax collection standpoint, the government is not able to monetize that benefit. Inflation is the easy way, even if it just delays the day of reckoning. All worth keeping in mind, I think , any time you hear an economist or politician prattle on.

As a last anecdote, the author speculates that $9,000 per ounce for gold is closer to fair value given the global money supply.

Thursday, April 24, 2014

From the Pile

Some recent books…

(1) When Money Dies by Adam Fergusson (1975, 2010). The subtitle is The Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation, and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany. We’ve covered this ground before and the story remains the same. When confronted with unsustainable finances (from war, from reparations, from subsidies), politicians are unable to make tough choices, and invariably have special interests that also stand in the way. The solution is the printing press and a move away from money that is backed by gold. Under such circumstances, labor trumps and professions that require a modicum of brain power (instead of heft) suffer. All of these dynamics made worse when the French and Belgians march into the Ruhr as a claim on what they were owed related to the Great War. Firms were forced to print their own money as an emergency measure when there was not enough currency to go around, and the Reichsbank accepted it, all of which enflamed the inflationary embers. Not surprisingly, we see a rise in extremism on the one hand (Hitler made his introduction to the German scene during this period), and a deferral to authoritarianism as the only hope for salvation on the other (with Democracy viewed more dismissively).

All of this finally resolved when a new currency (the Rentenmark) was introduced, tied to both gold and the dollar. It was a confidence trick, which speaks to how psychology is so important to the markets. In looking at the aftermath, while everyone lost, those who had gold or stable currencies fared much better – and with hindsight, it was clear that the hoped for inflation did nothing to resolve the debt burdens that existed before. There was pain before and after – all of it just exacerbated because of the delay in getting to the “after”.

(2) Rethinking the Great Depression by Gene Smiley (2002). A lot of the author’s work resembles the “regime uncertainty” thesis of Robert Higgs (how New Deal programs inhibited investment and private enterprise). At the same time, he does show some sympathy for Keynesian theory.

Within the universe of what he examines, he confirms the notion that the gold standard did not cause the Great Depression – instead a main contributor was an inability for countries to recognize how much the money supply had expanded during WW1 as they tried to maintain the pre-war peg. Smiley also recognizes that the idea of sticky wages was a new and unusual phenomenon in the context of history – Keynes pushed for rigid wages, but it did not help the process of economic rejuvenation and caused the downturn to last even longer. When the bank holiday happened in 1933, the proposals associated with the re-opening of banks sound a lot like the TARP program from 2008 (point being, we never learn). The “Depression within a Depression” was largely brought about by higher reserve requirements demanded by the Fed and higher wages from increased unionization.

For me, the most interesting part is where Smiley undermines the whole “war prosperity” nonsense – that World War II somehow brought the country out of the depression. Of course unemployment went down by 7 million people when 9 million men were conscripted. And of course GDP will go up when government spending is added to its calculation – we note that rationing and price controls prevented consumers from actually partaking in that “boom”. We also know that inflation was understated due to those same control mechanisms – which also means that GDP was overstated. Simply put, the war had to end before anything resembling a real recovery could emerge.

(3) Building Tall by John Tishman (2011). The subtitle is My Life and the Invention of Construction Management. Interesting tale about the Tishman who spent his career in construction (as opposed to the segment of the family that formed Tishman Speyer). He was involved in building the Twin Towers, Epcot Center, Renaissance Center in Detroit, Hancock Tower in Chicago, and many other interesting projects. He definitely makes a compelling case for having a construction management firm involved in any project.

(1) When Money Dies by Adam Fergusson (1975, 2010). The subtitle is The Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation, and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany. We’ve covered this ground before and the story remains the same. When confronted with unsustainable finances (from war, from reparations, from subsidies), politicians are unable to make tough choices, and invariably have special interests that also stand in the way. The solution is the printing press and a move away from money that is backed by gold. Under such circumstances, labor trumps and professions that require a modicum of brain power (instead of heft) suffer. All of these dynamics made worse when the French and Belgians march into the Ruhr as a claim on what they were owed related to the Great War. Firms were forced to print their own money as an emergency measure when there was not enough currency to go around, and the Reichsbank accepted it, all of which enflamed the inflationary embers. Not surprisingly, we see a rise in extremism on the one hand (Hitler made his introduction to the German scene during this period), and a deferral to authoritarianism as the only hope for salvation on the other (with Democracy viewed more dismissively).

All of this finally resolved when a new currency (the Rentenmark) was introduced, tied to both gold and the dollar. It was a confidence trick, which speaks to how psychology is so important to the markets. In looking at the aftermath, while everyone lost, those who had gold or stable currencies fared much better – and with hindsight, it was clear that the hoped for inflation did nothing to resolve the debt burdens that existed before. There was pain before and after – all of it just exacerbated because of the delay in getting to the “after”.

(2) Rethinking the Great Depression by Gene Smiley (2002). A lot of the author’s work resembles the “regime uncertainty” thesis of Robert Higgs (how New Deal programs inhibited investment and private enterprise). At the same time, he does show some sympathy for Keynesian theory.

Within the universe of what he examines, he confirms the notion that the gold standard did not cause the Great Depression – instead a main contributor was an inability for countries to recognize how much the money supply had expanded during WW1 as they tried to maintain the pre-war peg. Smiley also recognizes that the idea of sticky wages was a new and unusual phenomenon in the context of history – Keynes pushed for rigid wages, but it did not help the process of economic rejuvenation and caused the downturn to last even longer. When the bank holiday happened in 1933, the proposals associated with the re-opening of banks sound a lot like the TARP program from 2008 (point being, we never learn). The “Depression within a Depression” was largely brought about by higher reserve requirements demanded by the Fed and higher wages from increased unionization.

For me, the most interesting part is where Smiley undermines the whole “war prosperity” nonsense – that World War II somehow brought the country out of the depression. Of course unemployment went down by 7 million people when 9 million men were conscripted. And of course GDP will go up when government spending is added to its calculation – we note that rationing and price controls prevented consumers from actually partaking in that “boom”. We also know that inflation was understated due to those same control mechanisms – which also means that GDP was overstated. Simply put, the war had to end before anything resembling a real recovery could emerge.

(3) Building Tall by John Tishman (2011). The subtitle is My Life and the Invention of Construction Management. Interesting tale about the Tishman who spent his career in construction (as opposed to the segment of the family that formed Tishman Speyer). He was involved in building the Twin Towers, Epcot Center, Renaissance Center in Detroit, Hancock Tower in Chicago, and many other interesting projects. He definitely makes a compelling case for having a construction management firm involved in any project.

Wednesday, April 23, 2014

Cheerleaders

Color me confused. In an article about disappointing U.S. home sales figures, the author put the following two sentences in sequence:

"Existing home sales are counted at the closing of contracts and March's sales reflected contracts signed in January and February, when the country was in the grip of an unusually cold and snowy winter.

Home resales rose in the Northeast and Midwest, but fell in the West and South."

He is either clueless or incredibly sarcastic.

"Existing home sales are counted at the closing of contracts and March's sales reflected contracts signed in January and February, when the country was in the grip of an unusually cold and snowy winter.

Home resales rose in the Northeast and Midwest, but fell in the West and South."

He is either clueless or incredibly sarcastic.

Tuesday, April 22, 2014

Setting Sun

I pay close attention to Japan, so this Bloomberg article about the widening trade deficit is interesting. I liked this quote from economist Junko Nishioka at RBS: “In spite of the continued weaker yen, the performance of Japanese exporters is quite weak compared to competitors like Korea or Taiwan.”

This next one from Bloomberg highlights how inflation in Japan has picked up, but consumer confidence has dropped, because there has been no rise in wages to offset the inflation. So much for inflationary “benefits”.

Things don’t look so good for Shinzo.

Also, thought the chart below from the New York Sun tells a worthwhile story. It looks at income inequality in the U.S. – interesting what coincides with the spike up that starts in 1971…

This next one from Bloomberg highlights how inflation in Japan has picked up, but consumer confidence has dropped, because there has been no rise in wages to offset the inflation. So much for inflationary “benefits”.

Things don’t look so good for Shinzo.

Also, thought the chart below from the New York Sun tells a worthwhile story. It looks at income inequality in the U.S. – interesting what coincides with the spike up that starts in 1971…

Monday, April 14, 2014

Term of the Day

"Specious Pettifoggery"

It comes courtesy of David Stockman and should be used to describe any instance when a politician, mainstream economist or mainstream journalist is moving his or her mouth.

It comes courtesy of David Stockman and should be used to describe any instance when a politician, mainstream economist or mainstream journalist is moving his or her mouth.

Friday, April 11, 2014

Next in the queue...

Gold.

After tackling the currencies earlier, we now look at my favorite metal from the table of elements. I have never been a guy who focused on Fibonacci retracements, but, holy moly, does the gold chart confirm that analysis lately. First, here’s the chart (using GLD as a proxy):

Let me explain what’s going on. I have connected the trough of $114.46 on 12/31/13 with the peak of $133.69 on 3/14/14 – represented by the white, hashed line. Off of that, I have added Fibonacci fan lines (the dark blue lines), which measure the important Fibonacci retracement levels of 38.2%, 50.0%, 61.8% and 100.0%. What you’ll observe is that the correction from March 14th until April 1st matches perfectly with the 38.2% level. More specifically, the green arrow highlights where the 38.2% level lies – and in drawing a horizontal line from that point, you’ll see that the correction ended exactly at that price.

Pretty remarkable. And probably a decent sign that the near-term correction in gold was over.

As an afterthought, the light blue lines show the Fibonacci retracement levels for the move up off the April 1st low, and they suggest that we could be getting close to the next short-term pause in the price action.

After tackling the currencies earlier, we now look at my favorite metal from the table of elements. I have never been a guy who focused on Fibonacci retracements, but, holy moly, does the gold chart confirm that analysis lately. First, here’s the chart (using GLD as a proxy):

Let me explain what’s going on. I have connected the trough of $114.46 on 12/31/13 with the peak of $133.69 on 3/14/14 – represented by the white, hashed line. Off of that, I have added Fibonacci fan lines (the dark blue lines), which measure the important Fibonacci retracement levels of 38.2%, 50.0%, 61.8% and 100.0%. What you’ll observe is that the correction from March 14th until April 1st matches perfectly with the 38.2% level. More specifically, the green arrow highlights where the 38.2% level lies – and in drawing a horizontal line from that point, you’ll see that the correction ended exactly at that price.

Pretty remarkable. And probably a decent sign that the near-term correction in gold was over.

As an afterthought, the light blue lines show the Fibonacci retracement levels for the move up off the April 1st low, and they suggest that we could be getting close to the next short-term pause in the price action.

FX Trades

I don’t pay as much attention to the markets these days – but when I do, my focus is primarily on rates, forex and gold. Today we’ll hit on some currencies because they present interesting trades on a regular basis, with the ability to use options on ETFs in order to implement ideas and manage risk.

First up is the Euro. I saw this article about how Draghi and ECB members are getting worried about deflation, with the single currency getting stronger against the US Dollar. Arguably the ECB has been the least aggressive in its monetary policy and, as a result, the Euro is up near 1.40 (after being as low as 1.275 last August). Which is why I fully expect some action in the next few months, consistent with the piece from Bloomberg. And why I think it is time to get positioned with some puts on the FXE.

Next is the Yen. I posted a few weeks ago about a cup-and-handle in the chart, foretelling Yen weakness ahead. Given the difficulties that Abenomics has had in achieving its goal. I fully anticipate more JGB purchases by the BOJ. Even the chart suggests that the Yen is at support levels and unlikely to get much stronger from here. My play is to purchase puts on the FXY.

Clearly both trades would suggest dollar strength ahead. And while the Dollar Index has been getting hammered lately, it’s approaching levels that have functioned as support in the past.

First up is the Euro. I saw this article about how Draghi and ECB members are getting worried about deflation, with the single currency getting stronger against the US Dollar. Arguably the ECB has been the least aggressive in its monetary policy and, as a result, the Euro is up near 1.40 (after being as low as 1.275 last August). Which is why I fully expect some action in the next few months, consistent with the piece from Bloomberg. And why I think it is time to get positioned with some puts on the FXE.

Next is the Yen. I posted a few weeks ago about a cup-and-handle in the chart, foretelling Yen weakness ahead. Given the difficulties that Abenomics has had in achieving its goal. I fully anticipate more JGB purchases by the BOJ. Even the chart suggests that the Yen is at support levels and unlikely to get much stronger from here. My play is to purchase puts on the FXY.

Clearly both trades would suggest dollar strength ahead. And while the Dollar Index has been getting hammered lately, it’s approaching levels that have functioned as support in the past.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Broken Money

The subtitle is Why Our Financial System is Failing Us and How We Can Make it Better , and the author is Lyn Alden (2023). I feel like I hav...

-

Are when the contrarian should think about buying. And so I tried. Some AUY LEAPS (filled) and a small mining services company that I like...

-

I came across this really interesting chart regarding 2013 and 2014 EPS forecasts by region and globally. Note the very pronounced move fr...

-

Apropos the book that I just finished, I re-visited an interview from September with Kyle Bass, where he examines many of the same themes ...